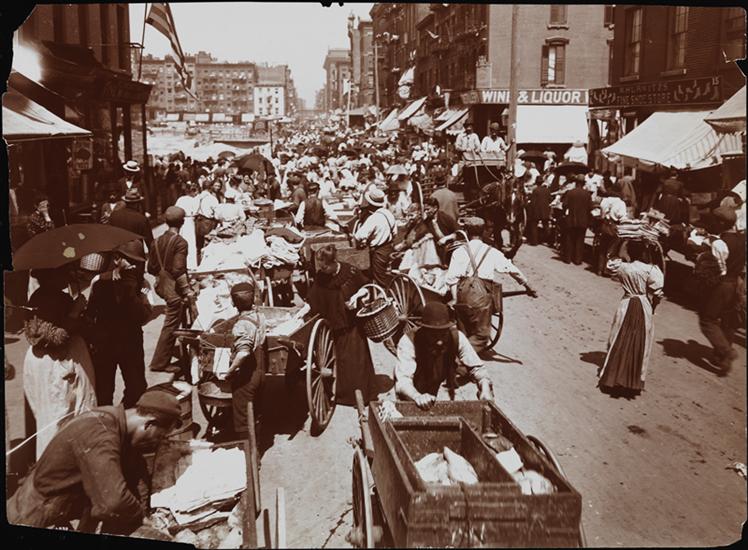

Business on Hester Street had concluded for the day of September 29, 1892. Just a few hours earlier, the thoroughfare, named after Hester Leisler, was rife with fruit stands, crowded garment shops and peddlers displaying their wares. Approaching 7:00pm, the Thursday temperature dipped slightly to a cool and fair 68 degrees as twilight was underway. Save for a few stragglers, the busy shopping district turned dormant.

139 Hester Street lay nestled between Bowery and Chrystie Street. The building was like any other tenement house: a four story walk-up, dimly lit and crammed, occupied by mostly renters who lived in single rooms, a true hallmark of life on the Lower East Side. In the young evening, after the crowds dispersed and a light fog settled over the Bowery, a slender young man appeared in front of the building. Donning a felt hat and carrying a small metal instrument, he would made his way up the creaking staircase to the door of a small room on the top floor. A light knock echoed like thunder to the occupier on the other side.

Kleindeutschland, or Little Germany was the name given to the area of the Lower East Side from Division Street to 14th Street and Bowery to Avenue D. By the mid to late 19th century, Manhattan’s Kleindeutschland was the third largest “German” city in the world, behind Berlin and Vienna. In fact, by 1870, 30% of New York City was comprised of German immigrants or residents of German descent. The majority of the working class German immigrants settled in the inexpensive tenement houses dotting the Lower East Side. Known for being very skilled and meticulous in their craft, German immigrants took great pride in their trades. The majority of bakers, tailors, cigar makers, shoemakers, and carpenters were comprised of Germanic surnames. One such carpenter was Frank G. Paulsen.

A native of the German state of Saxony, Frank Paulsen was born in 1837 and became skilled in carpentry at a young age. He arrived in New York City in the late 1850s, and like most Germans, settled in the 10th ward of the Lower East Side. With the Civil War in its early stages, Paulsen enlisted in the Union army and became a member of the 20th Regiment in the New York Infantry on May 3, 1861. He attained the rank of sergeant a year later and was discharged on February 14, 1863. Returning to his wife Camille, he took a job as a waiter while living on Chrystie Street. He would remarry in 1868 to Sophia Schirmeister, move to Broome Street and also become a naturalized citizen. By 1892, Frank was unemployed but had managed to save a decent amount of money while earning a pension from his Civil War service. This was evident by his practice of always wearing two watches; one, a pocket watch and the other a wristwatch. At this time, the Paulsen’s living arrangements had changed. Although they were still married, the couple lived in separate residences. Sophia and their daughter were living at a hotel in Brooklyn where she was employed as a cook, while Frank stayed on the Lower East Side at 139 Hester Street.

Frank Paulsen answered the knock at his door about 7:30pm. Standing in front of Paulsen was a young man of slender build. His felt hat slightly covered his aquiline nose, bony face and deep sunken black eyes that burned like coals. Paulsen invited the visitor in as he was familiar with him, though he did not notice the object he was carrying in his right hand. Within minutes, sounds of a struggle and horrific screams echoed throughout the four story flat. William Burns, a neighbor of Paulsen instantly opened his door and observed the slender man run down the stairs toward the building’s front entrance. Burns looked out his window and observed the man sprinting down Hester Street, disappearing onto the Bowery. Burns ran into Paulsen’s room, encountering a gruesome scene. Blood splattered walls surrounded 55 year old Frank Paulsen, slumped over a chair, with seven deep wounds that completely smashed his head in. In shock, Burns ran to get a patrolman and give a description of the man who ran from his neighbor’s room.

While the coroner collected the body of the deceased, authorities determined that two gold watches, rings and other assorted jewelry were missing from Mr. Paulsen’s apartment. At 10:30 pm, Officer Emanuel Meyer of the Eldridge Street station house was notified of a disturbance involving an intoxicated patron at a saloon on 15 First Street, off of the Bowery. While saloons lined the infamous strip and drunken patrons were a common occurrence, the subject of this call was also illegally selling jewelry.

Frank W. Roehl was a 26 year old marble trimmer arrived from Germany in the early 1880s. Although he lived in a boarding house in Hoboken, NJ, he would often visit his uncle at his home in College Point. While in New York, Roehl would often frequent the many saloons of the Bowery. It was in one of these saloons in 1889 where he became friendly with old Frank Paulsen. While not best of friends. they would remain acquaintances over the next three years usually meeting over pints of ale. Roehl had separated from his wife and while in between marble jobs, was usually in trouble with the law. He racked up numerous arrests for robbery and assault, and spent time in the Essex Police Court on many occasions.

As Officer Meyer approached 15 First Street, he observed Frank Roehl in a drunken stupor outside of the saloon displaying watches and money to passersby. Meyer began to question Roehl on what he was doing. Roehl explained the watches belonged to him and that he bought them from a jeweler uptown six months ago. As the El rumbled over the Bowery, an agitated Roehl from his trousers, withdrew a small axe covered in blood and took a swipe at Meyer. Luckily, the patrolman was able to dodge the swing and strike Roehl’s wrist with his nightstick. The hatchet and watches dropped and a struggle ensued, taking four patrolmen to gain control of Roehl and effect an arrest. William Burns and his wife were at the 11th Precinct Station House at 105-107 Eldridge Street when the officers bought Roehl in for booking. Mr. Burns was able to identify Roehl as the young slender man running from Frank Paulsen’s room just a few hours earlier. Mrs. Burns recognized the two watches and various rings as belonging to their neighbor as she would clean and polish his jewelry when asked. Inspector Williams considered the statements of Mr. and Mrs. Burns along with the hatchet as enough evidence to charge Frank Roehl with first degree murder. Roehl responded that he never knew Frank Paulsen and other untruthful statements before finally confessing to the killing, but in self defense.

On December 16, 1892 before Judge Martine in the Court of General Sessions, Roehl’s lawyer E.T. Goldberg entered a plea of self defense instead of insanity. Goldberg’s case was that on September 29, 1892, Frank Roehl was asked by Alvina Kadian, wife of the boarding house owner where Roehl lived, to go to the woodshed and chop some wood. Roehl complained that the hatchet was too dull and that he would go to New York to get the hatchet sharpened at the factory where he used to work on 48th Street. Roehl arrived too late to the factory, deciding to spend the evening in town. Not wanting to carry the hatchet with him, he decided to leave it with his friend, Frank Paulsen. An intoxicated Paulsen answered the door and invited Roehl in for drinks. Their conversation quickly grew heated as Roehl stated that Paulsen made a disparaging remark toward Roehl’s ex-wife. Paulsen knocked Roehl down and proceeded to choke him. Feeling his life slip away, Roehl could only grab the nearby hatchet and swing it at Paulsen. Paulsen went unconscious. Nervous and not knowing what to do, Roehl went to a nearby saloon and started to drink.

The prosecution told a different story. Mrs. Kadian explained how she never asked Roehl to chop wood and instead she noticed the hatchet was missing from the woodshed. Mr. Kadian was able to identify a ring that was missing from his nightstand which was found on Roehl’s person the night of his arrest. It was determined that Roehl had owned a debt to a saloon owner and knowing that his friend Frank Paulsen had money and expensive jewelry, he would rob Mr. Paulsen. Assistant DIstrict Attorney McIntyre went a step further to prove Roehl’s vicious temper. He questioned Roehl’s relationship with his wife, to which the defendant sprang at McIntyre and tried to grab his throat. Roehl was held back by court officers as the trial was brought to a close. It took the jury just 35 minutes to find Roehl guilty of murder. As if not punishment enough, Roehl’s father, who was on a steamship en route to New York from Hamburg to support his son passed away. Later in the month, Roehl would be sentenced to death.

Frank Roehl arrived at Sing Sing Prison in Ossining, NY on January 20, 1893. He struck up a friendship with fellow inmate and murderer Thomas Pallister. Pallister was convicted of killing Probationary Police Officer, Adam Kane on April 30, 1892. He was a skilled construction worker, but like Roehl, was always on the wrong side of the law. Thomas Pallister was very familiar with Sing Sing Prison. He was part of a group of workers that constructed the infamous “Death House.” Knowing the layout of the prison presented a great opportunity to Pallister and Roehl…rather than face “Old Sparky,” why not escape? On April 20, 1893 they did just that.

Pallister knew of a hatch on the roof of the Death House that was not secure. They just needed to find a way to get out of their cells. Guard duty was light the evening their plan went into effect. Pallister asked Night Watchman Hulse if he could heat up his dinner for him in the stove because his serving of meat was cold. The guard obliged and returned with a heated dinner. Because the bars were too narrow to fit the tray, the guard opened the cell door and pass off the tray. Pallister sprung into action and threw a handful of black pepper into the guard’s eyes. He overpowered Hulse, disarmed him of his revolver and cell keys, and locked Hulse in the cell, threatening to shoot him if he made any noise. Pallister freed Roehl and locked another guard in Roehl’s cell. They made their way to the hatch on the roof and noticed the conditions outside were hurricane-like. This proved in their favor as the outside tower guards were inside for cover. The pair went through the hatch and scaled down the wall onto safe ground outside the north end of the prison. They were able to obtain a small rowboat near the shore and slip away in the darkness. During the investigation of the escape, it came to be known that ten days prior a man who said he was Frank Roehl’s brother arrived in New York City from Germany. He appeared at the law offices of Goldberg & McLaughlin carrying a briefcase containing $7000 and informed Roehl’s lawyer that he would be going to Sing Sing. Did this mysterious brother play a role in the escape?

On May 10, 1893 Frederick Cronk was pulling in his nets during a morning of fishing when he noticed something floating near the shore of the Hudson River. As he got closer he noticed it was a body. Knowing the news of the prison escape a few weeks ago and the outstanding reward, he tied a rope around the body and pulled it ashore. The authorities responded and immediately recognize the prison clothes and shoes. The skull was severely fractured and contained a bullet hole on the right side. Dental identification was made. The body was identified as Frank W. Roehl. Six days later the body of Thomas Pallister was found floating in the Hudson near Croton Point. Pallister also had a bullet wound to the head. The end of two vicious murderers ended viciously. It was determined, but not certain, that Roehl and Pallister got into an argument and Pallister shot Roehl in the head and dumped his body. Pallister then fearing he would be caught, took his own life. Frank Roehl, the murderer of Frank Paulsen would be buried on top of a hill in the small Sing Sing Cemetery. Thomas Pallister would be buried with his parents in Calvary Cemetery.

Driving around Middle Village, Queens, I entered All Faiths Cemetery, formerly known as Lutheran Cemetery. Making my way to Public Section 1 on the Northside, I discovered grave number 96 in row 15. The only military headstone in the vicinity read:

SGT FRANK PAULSEN

CO.H

20 NY INF

I cleaned off the moss and brushed away the leaves and thanked him for his service.

Michael is a New York City history buff, amateur genealogist, and a member of the New York law enforcement community. His NYC roots go back to 1820 on Water Street and the Vinegar Hill section in Brooklyn.