Chinatown is a beautifully vibrant neighborhood cradled within the traditional boundaries of New York City’s Lower East Side, filled with friendly restaurants, street vendors, and gift shops. The district has long been associated with a rich cultural heritage, delicious cuisine, and a bustling street life. However, beneath the surface, Chinatown — like most ethnic neighborhoods — has a rich history of organized crime, with various gangs and organizations vying for control and power.

The Roots of Chinatown in New York City

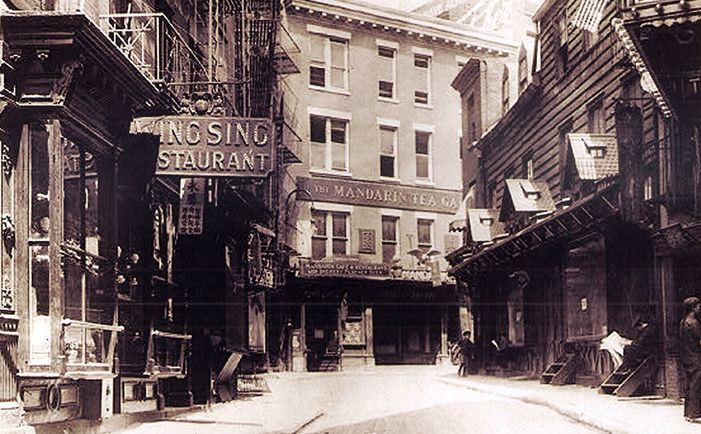

The original Chinese enclave, “Old Chinatown,” was carved out in the 1860s — pre-dating mass immigration of Italians and Eastern Europeans to the district by a couple of decades. By all accounts, the spark was a man named Ah Ken, who sold cigars around City Hall and eventually opened a boarding house at 13 Mott Street, which hosted Cantonese-speaking workers migrating to the city after gold-mining and rail road jobs dried up out west.

Though the Chinese Exclusionary Act prevented most Chinese nationals from immigrating to America after 1882, there was still a fascination with the so-called “exotic” Far East, so people from all walks of life poured into Chinatowns across the country to get a glimpse of a faraway land they could only read about in newspapers and magazines. Business-savvy Chinese entrepreneurs took advantage of this and turned the district into a tourist trap from nearly Day One — with restaurants, trinket shops, and yes, vice.

Without spending too much time on U.S. policies over the next century, Chinese did not start migrating to the States in large numbers until after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. It was then that the Chinese population in New York City began to grow rapidly. By the 1970s and 80s, the district was no longer dominated by Cantonese, but migrants from several provinces poured in, which may have created some tension with language and cultural barriers.

The Emergence of Organized Crime in Chinatown

Organized crime in Chinatown dates back to the late 19th century, as gangs fought over the profitable gambling parlor and opium den businesses which attracted tourists and thrill seekers from all over the country and beyond. Century-old Chinese associations known as “tongs” took advantage of the expanding community and established themselves as the de facto authorities in the neighborhood. These tongs controlled both legitimate and illicit activities, including extortion, gambling, and loan sharking, effectively exerting control over the local businesses and residents.

The Opium Trade

Opium became a highly lucrative comodity by the late 19th century, and the drug was already fairy common among people from many walks of life by the time Chinese gangsters created a monopoly on its distribution. According to reports, about 20,000 pounds of the product was consumed (eaten, smoked, drank, injected) in America in 1840, however, by 1880, it was estimated to have ballooned to over 500,000 pounds.

The best opium, referred to as “hop” and labeled as “No. 1,” was imported from Hong Kong. It cost consumers about $8 per pound and had brand names like Fook Yuen (“Fountain of Happiness”) and Li Yuen (“Fountain of Beauty”). Lesser quality brands were smuggled in from British Colombia by French women who the Chinese employed as mules. These brands were labeled as Ti Yuen, Ti Sin, Wing Chong, and Quan Kai.

By the end of the century, there were dozens of opium dens, referred to as “joints,” in and around Chinatown. Most all of them were tucked away in dark, guarded tenements, wherein customers needed a “guide” to traverse the dimly-lit maze of hallways, courtyards, alleys and steps which brought them to a barricaded basement room where 15 to 20 other consumers would be scattered about in near darkness. Along the sides of the rooms were lifted platforms, along with a block of wood to lay your head. Upon payment, an attendant would bring you a “lay out,” which included the opium and all of the paraphernalia one may need to imbibe.

Not only was the primary industry of opium sales highly profitable, but entire secondary industries kept many a family fed: pipe repair was one way to make a living, and so was collecting ash at the end of the day, which one can “cut” with pure opium and be resold to lesser dens as “No. 2 opium,” or “Yen She Kow (“half and half”).

Highbinders, Human Trafficking and Prostitution

In the 19th century, Americans referred to the criminal class of Chinese immigrants as “highbinders.” These were generally men who engaged in such heinous crimes as murder- or violence-for-hire and the trafficking of women for the purpose of prostitution. At the time, the most relevant highbinders were organized under the umbrella of the Hip Sing Tong, which had about 450 feared members.

Prostitution was rampant in immigrant communities throughout New York City by the end of the 19th century. By the 1910s, 75% of all prostitutes brought before the local magistrate were from the Jewish quarter. In fact, in Chinatown, the majority of prostitutes were also women of European decent who were largely drawn by the calling of opium. Chinese women as young as 15-years old were also bought, sold and traded for both prostitution and marriage for as little as $700, and some as high as $2,000. They would often be under involuntary contract to provide services for two or three years before being able to afford their freedom.

As a custom, these prostitutes were not allowed to leave their dwellings, so it was a common scene along Mott, Pell, and Doyers Streets to see Low Gui Gow (“common woman’s dog”) — “white, black and yellow” boys who ran errands for the women and helped bring in business. Introducing a pretty woman to a client could fetch a street kid half of a dollar, while securing opium or even a beer could fetch a tip of 5 to 25 cents.

Almost everyone was finding a way to make money off of the vice that was dominating the district, including the police who were paid to be indifferent. And it was all overseen by the tongs to be sure that all of the wheels were in motion, and problems were kept to a minimum.

The last publicly-known opium den in NYC was raided and shut down on June 28, 1957, on the second floor of 295 Broome Street. Confiscated was only 10 ounces of opium and 40 ounces of heroin. Unbeknownst at the time, this signaled the end of the nearly century-long opium trend, and the beginning of the more modern heroin culture, so popular with jazz musicians, poets and artists of the era.

The 1980s and the Heroin Connection

In the early 1980s, a significant shift occurred within Chinatown’s criminal landscape. The leaders of the traditional tongs seemingly sought more lucrative ventures, leading them to enter the heroin trade. This transition marked a turning point for Chinese organized crime, as they began to compete with established Italian and black organized crime families as primary suppliers of heroin in the New York City. The sudden influx of heroin further fueled the power and influence of the tongs and their associated gangs.

Robert M. Stutman, who was the lead investigator for the New York office of the Drug Enforcement Administration which cracked the infamous “French Connection” case in the 1960’s, stated, ”These Chinese make the French Connection look like second-raters.” He continued, “The Chinese moved into heroin (quickly), replacing traditional Sicilian organized-crime families. In 1983, Chinese dealers accounted for only 3 percent of the supply in the city. By 1989 they provided 75 percent.”

This newfound fortune also brought competition, and violence. Several street gangs emerged, supported by various tongs and associations: Ghost Shadows, Black Eagles, Liang Shan, The Chung Yee, and the White Eagles, to name a few. Even as a kid growing up in the 1980s and 90s, I knew “Not to mess with the Chinese kids,” even though most everyone I knew had Genovese- or Gambino-family ties. This was an era when New York City was a powder keg.

And for the first time, Vietnamese gangs began to challenge the Chinese in their own territory. Shootings and bombings were becoming common occurrences in this once stable community and both the tongs and police had a difficult time keeping a lid on the violence. From this chaos emerged charismatic, yet cold-blooded leaders which led Chinatown into a new era.

Johnny Eng: A Criminal Mastermind

Among the key figures in this new era of organized crime in Chinatown was Johnny Eng. His nicknames were “Machine Gun” Johnny Eng and Onion Head. Born in Hong Kong, Eng moved to New York City with his parents at the age of 14. In his early years, he engaged in street-level criminal activities, extorting money from restaurants alongside his juvenile gang. Eng’s reputation caught the attention of Benny Ong, a prominent figure in Chinatown and feared leader of the Flying Dragons street gang, who took him under his wing.

Eng’s path to gang leadership took an unexpected turn when he pursued a career in acting as a teenager. Ironically, his favorite movie was apparently the 1983 crime film Year of the Dragon, set in New York’s Chinatown and staring Mickey Rourke and fellow Hong Kong-born actor, John Lone, as a young, well-dressed, and educated mobster. Lone’s character is said to have resonated with Eng, who shared similar characteristics.

Eng’s involvement in the heroin trade proved to be highly profitable, amassing him untold wealth. Once he started making money, he was rarely seen in Chinatown. He owned an $800,000 mansion on Staten Island and a farm in Pennsylvania, showcasing his opulent lifestyle. In Hong Kong, he resided in luxury apartments and frequented exclusive clubs and golf courses. Eng’s business ventures extended beyond drugs, with interests in the local film industry, diamond trading, and shipping, providing many avenues of money laundering for his partners.

Eng’s criminal empire eventually caught the attention of law enforcement agencies, both in the United States and Hong Kong. He was arrested and indited in 1989 for trafficking more than 150 pounds of heroin into the United States, along with several members of his crew, including Michael “Fox” Yu, the Flying Dragon’s underboss. Though he fled the country, Eng was arrested in Hong Kong and extradited back to the United States in 1991 to face multiple charges related to heroin smuggling and distribution.

In December 1992, Eng stood trial in New York City, facing 14 counts of heroin smuggling and conspiracy. The evidence presented against him was overwhelming, including the seizure of a significant amount of heroin linked to his operations. Eng was convicted on all charges and sentenced to 24 years in prison. The judge also imposed a hefty fine of $3.5 million and confiscated Eng’s assets, including his lavish properties.

Upon Eng’s release in 2010, he quickly disappeared, and is now apparently in China and doing business with another former Flying Dragons member who was deported after spending time in prison.

The Dominoes Fall

In March of 1990, the D.A. indicted Chung Chi-Fu, AKA Khung Sa, accused of running a multi-million dollar heroin ring out of Thailand, Laos and Myanmar with a direct route to consumers in New York City.

Later that year, a joint FBI investigation netted 40 individuals in “Operation Whitemare,” including Han Sho Wei, one of the most prominent female smugglers in American history up until that time.

By 1991, the trafficking operation of Kelvin Lee and Suen Man Tang was brought down by the government.

The Legacy of Chinatown’s Criminal Underworld

The influence of the tongs and their associated gangs allegedly continue to shape the neighborhood’s dynamics. Extortion, gambling, illegal lotteries, loan sharking, and possibly drug and human trafficking remain prevalent, according to authorities and inside sources that I have interviewed. Though we may never know, because it is nearly impossible for a non-Chinese outsider to open a business, or even rent an apartment in a district so heavily governed by local oversight, as 150 year old tongs allegedly still hold court over the community.

As Chinatown continues to evolve, the increasing population of Chinese immigrants presents both opportunities and challenges. The majority of Chinese immigrants moving to New York City’s Chinatowns (Lower East Side, Flushing, Sunset Park, etc.) are lower-wage laborers and restaurant workers with no connections or political power, and easily taken advantage of. This continues to provide fertile ground for criminal enterprises, with gangs preying on businesses and residents alike.

Law enforcement agencies, such as the Manhattan District Attorney’s Asian Gang Unit, continue their efforts to combat organized crime in Chinatown. Through targeted investigations, arrests, and prosecutions, they aim to dismantle these criminal networks and restore safety and order to the community.

Conclusion

Chinatown, a vibrant and culturally significant neighborhood in New York City, has a complex and troubled history when it comes to organized crime. From the reign of tongs and their associated gangs to the rise and fall of figures like Johnny Eng, the criminal underbelly of Chinatown has left an indelible mark on the community.

However, make no mistake. This is one of the safest neighborhoods in New York City and tourists and outsiders should have zero qualms about visiting and shopping. The overwhelming majority of people you will encounter will be some of the friendliest and honest people you will ever meet. Any behind-the-scenes politics has zero affect on outsiders. Even criminals want to make you feel safe so you spend your money here.

One last tip: while visiting, if you want authentic Chinese food, stay away from the touristy places. (Sorry Wo Hop, I’m talking about you.) My advice? If you see all non-Chinese people inside or on line, move on to the place without an Instagram page and all the Asian patrons. Enjoy!

[Special thanks to Michael Moy for the feedback. Michael is one of the preeminent experts on Chinatown gangs and you can find his in-depth work here on Youtube. Also thank you to the active insiders for sharing their knowledge.]

Eric is a 4th generation Lower East Sider, professional NYC history author, movie & TV consultant, and founder of Lower East Side History Project.